Hypoglycemia: What is the danger for patients with Type 1 Diabetes?

Article

Content

Introduction

Last time we discussed the state of hyperglycemia, which is an elevated level of blood glucose. This is the most common problem faced by parents of a child with a recently diagnosed diabetes or with a long history of diabetes but with poor compensation. In this article, we will talk about the exact opposite situation – low blood sugar levels, which rarely appear on the glucometer.

Threshold Level of Hypoglycemia

The term "hypoglycemia" literally means "low blood sugar." It is a pathological condition where the concentration of glucose in the blood falls below the normal threshold. For an individual without diabetes, this ranges from 52 to 61 mg/dL (from 2,9 to 3,4 mmol/L) and is considered to be 61 to 70 mg/dL (3,4 to 3,9 mmol/L) for patients with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D). When blood glucose concentration drops below this level, metabolism in all cells and tissues of the body is disrupted. Consequently, pediatric endocrinologists consider a blood glucose level of 72 mg/dL (4 mmol/L) to be the threshold for preschool-aged children or those with less than a year of diabetes experience.

At the onset of diabetes, the body gets accustomed to high glucose levels, so a drop to normal blood sugar levels is perceived as a catastrophe, presenting a vivid picture of hypoglycemia, even if the blood glucose level is normal. Moreover, due to the metabolic characteristics in childhood, hypoglycemia develops rapidly, is more difficult to manage, and leaves more consequences for the developing nervous system. Because of the life-threatening complication of hypoglycemia, target blood glucose levels are shifted towards higher values.

On the other hand, it is noteworthy how over the 100 years since the invention of insulin, the only effective treatment for T1D, the requirements for diabetes compensation have become stricter. Previously, the absence of glucose in the morning urine test was considered a victory over the disease (glucose appears in urine at blood concentrations of 144 mg/dL (8 mmol/L) and above). Now, the goal of diabetologists and patients is to maintain blood glucose concentrations within target ranges most of the time, without episodes of fluctuations into hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia.

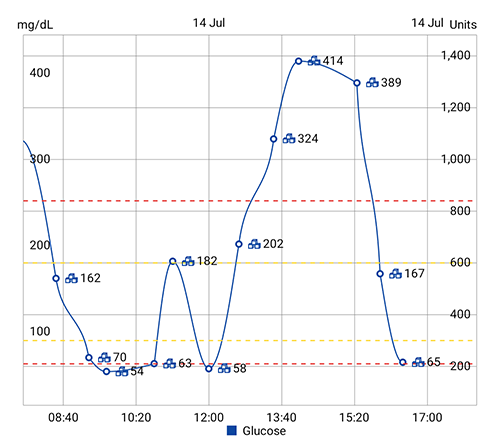

In healthy individuals, fasting blood glucose levels do not exceed 100 mg/dL (5.5 mmol/L) in capillary blood, and two hours after eating, they do not exceed 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L). Ideally, a patient with diabetes should aim for the same level of glycemia, allowing rises up to 200 mg/dL (11 mmol/L) after meals. However, maintaining blood glucose levels close to normal is often associated with the risk of hypoglycemia. A patient with diabetes receiving insulin constantly balances between complications due to hyperglycemia and possible hypoglycemia. The risk is especially high in children and adolescents with their fluctuating metabolism and sudden hormonal surges that regulate glucose metabolism. Adult patients with stable metabolism are less prone to sugar spikes and the risk of hypoglycemia, but the consequences for them are just as dangerous as for children and adolescents.

Nature of Hypoglycemia

Factors contributing to the development of hypoglycemia:

Disruptions in the insulin therapy regimen (overdosing, especially of nighttime basal insulin),

Inadequate intake or absorption of glucose (errors in diet or accompanying illnesses, intestinal infections, etc.),

Increased glucose consumption (physical activity and sports),

Alcohol consumption,

Hormonal characteristics of childhood.

The central nervous system, the main consumer of glucose in our body, is responsible for most manifestations of hypoglycemia. Neurons, being the most sensitive cells to hypoxia and hypoglycemia, are the first to suffer.

Depending on the individual characteristics of the body, hypoglycemic syndrome can manifest in various ways:

Symptoms of Hypoglycemia

Altered consciousness, ranging from agitation and increased aggression to drowsiness

Anxiety and fear

General weakness and disorientation

Excessive sweating and muscle trembling

Irregular and rapid heartbeat

Increased or decreased blood pressure

Hunger

Nausea and vomiting

Headache and dizziness

Visual and speech disturbances

Impaired coordination of movements

Amnesia and seizure episodes

Fainting and coma

The severity of hypoglycemia not only depends on its current level but also on the average blood glucose level over the recent period to which the nervous system has adapted, as well as on the age and individual characteristics of the child.

Degrees of Hypoglycemia

The degree of hypoglycemia ranges from mild and moderate to severe, depending on the clinical symptoms accompanying the hypoglycemic state.

Mild Hypoglycemia

The person is conscious and can independently manage hypoglycemia by consuming easily digestible "fast" carbohydrates. Special tablets or gels of monosaccharide (D-glucose or dextrose) are best suited for this purpose, as they are immediately absorbed into the blood without prior breakdown. If necessary, the tablets can be replaced with a sweet drink such as Coca-Cola or sweet tea.

What to Do in Case of Mild Hypoglycemia?

Consume 5 – 10 grams of "fast" carbohydrates followed by monitoring blood glucose levels after 10 – 15 minutes.

Moderate Hypoglycemia

Symptoms are more pronounced, the person is still conscious, but blood glucose levels do not rise after consuming fast carbohydrates or may even continue to fall.

What to Do in Case of Moderate Hypoglycemia?

Consume another 5 – 10 grams of "fast" carbohydrates followed by monitoring blood glucose levels after 10 – 15 minutes.

If you manage to return the glucometer readings to normal values, consider the cause of the hypoglycemia. If you see signs of further glycemic decline (e.g., overdose of basal insulin or nausea and vomiting after administering the usual bolus insulin dose), you will need to add 10 – 20 grams of "slow," complex carbohydrates, such as a banana or a piece of bread, to the "fast" carbohydrates to prevent long-term glucose drops.

The cycle of "eating and measuring sugar" will need to be repeated until blood glucose levels are fully normalized.

Severe Hypoglycemia

The extreme form of hypoglycemia, life-threatening - coma; severe form - pre-coma state, where the person cannot manage the situation independently.

What to Do in Case of Severe Hypoglycemia?

For patients who are unconscious, the first aid is to administer the hormone glucagon intramuscularly, which quickly raises blood glucose levels (please consult your doctor and determine the dose of this medication in advance).

Our goal is the quick return of consciousness. After consciousness is restored, which should be expected within a few minutes after the injection, give the patient 10 - 20 grams of "fast" carbohydrates. Then follow the algorithm for moderate hypoglycemia.

In the case of severe hypoglycemia, it is necessary to call for emergency medical assistance while performing these measures. Intravenous administration of a 40% glucose solution leads to a rapid increase in blood glucose levels.

Forewarned is Forearmed!

Hypoglycemia is a serious complication that requires immediate intervention to prevent possible severe hypoglycemia. It is necessary to prepare in advance by gathering and storing an emergency supply in all places where the child regularly stays. This supply should include dextrose tablets or gels and an syringe pen with glucagon.

It is important to explain the symptoms of hypoglycemia and the process of managing this condition to all adults and children around the child with Type 1 Diabetes. In the event of hypoglycemia, there is no time to think; you must act quickly. Plan, write down, and memorize the order of actions in advance.

Until the hypoglycemia episode is recorded in the diabetes diary, the information is analyzed, and the cause of the hypoglycemia is identified, the episode is not over.

Mobilization of Hormones

It is difficult to quickly resolve an episode of hypoglycemia because it results in a normal physiological increase in blood glucose levels. This post-hypoglycemic hyperglycemia, colloquially known as the Somogyi effect, cannot be corrected with additional insulin injections. The body temporarily loses sensitivity to the usual doses of insulin.

Post-Hypoglycemic Hyperglycemia

To explain this phenomenon, it is appropriate to recall the saying "One man is no man". Normally, blood glucose levels are regulated contrary to this folk wisdom: one unique insulin lowers blood glucose levels, while many other hormones raise it. The situation where the body does not produce its own insulin has catastrophic consequences in the form of Type 1 Diabetes. Hypoglycemia is so threatening to our survival that nature has provided for the duplication of the important process of raising blood glucose levels. Besides glucagon, the pancreatic hormone we mentioned earlier as first aid, other hormones such as growth hormone, cortisol, adrenaline, thyroid hormones, testosterone, and estrogen also raise blood glucose levels. In response to the threatening drop in blood glucose levels, there is a release of growth and stress hormones, which prevent a decrease in glycemia for the next few hours. It is important to know about this effect and not to panic, uncontrollably injecting insulin without effect, swinging the pendulum from hypo- to hyperglycemia.

How do the aforementioned hormones (also called "counterregulatory hormones") raise blood glucose levels? Glucagon breaks down glycogen stores in the liver, while other hormones activate the formation of glucose from non-carbohydrate compounds. In the case of frequent hypoglycemic episodes, the body's glycogen, protein, and lipid (fat) stores are depleted. Thus, patients with prolonged decompensation of Type 1 Diabetes experience impaired mechanisms of protection against hypoglycemia in all directions.

The "Dawn Phenomenon"

In childhood and adolescence, when the endocrine system is most active, surges of counter-regulatory hormones cunningly complicate the selection of insulin therapy doses for endocrinologists and parents.

For example, the "dawn phenomenon" occurs when, in the early morning hours, both healthy children and those with Type 1 Diabetes experience an increase in blood glucose levels due to enhanced secretion of growth hormone – a powerful counter-regulatory hormone. In healthy children, insulin secretion is triggered, and blood glucose levels decrease. However, in patients with Type 1 Diabetes, their bodies do not produce insulin, requiring manual adjustments to the insulin therapy regimen in the morning hours.

As normal physiology of the endocrine system tells us, the "dawn phenomenon" and many other complexities will diminish by the age of 25 or even earlier when hormone surges decrease.

Wishing all readers targeted glycemia!